Bonnie Levine: How did you get started as a jewelry designer? Was there someone or an experience that inspired you?

Matthieu Cheminée: My mother had a beautiful jewelry collection from all around the world, pieces that my dad would bring back from trips. She had bracelets from Afghanistan, crosses from Ethiopia, pendants from Peru, and more. I had always been attracted to them but my passion for the trade really started when I went to Taos, New Mexico, to visit an aunt when I was 17. I fell in love with all the Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni jewelry. Just before I turned 19, I moved to Taos from Paris to learn English and ended up learning jewelry making with great artisans. For almost seven years I made stamped bracelets and concho belts and I learned inlay and overlay.

Bonnie Levine: How did you get started as a jewelry designer? Was there someone or an experience that inspired you?

Matthieu Cheminée: My mother had a beautiful jewelry collection from all around the world, pieces that my dad would bring back from trips. She had bracelets from Afghanistan, crosses from Ethiopia, pendants from Peru, and more. I had always been attracted to them but my passion for the trade really started when I went to Taos, New Mexico, to visit an aunt when I was 17. I fell in love with all the Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni jewelry. Just before I turned 19, I moved to Taos from Paris to learn English and ended up learning jewelry making with great artisans. For almost seven years I made stamped bracelets and concho belts and I learned inlay and overlay.

You use ancient techniques such as stamping and casting in your work. Why are you drawn to these techniques?

Matthieu Cheminée: Stamping is the first thing I learned; I like how simple and fast it can change a sheet of metal. I also love the freedom of it—it can be done anywhere. All it takes is a piece of steel that can be transformed into a stamp, a hammer, and an anvil. I was amazed when one of my stamped bracelets was chosen for a show at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal featuring contemporary jewelry. I love that an ancient and universal technique such as stamping is seen as contemporary. This shows that techniques transcend time.

In addition to these ancient techniques, you also use contemporary CAD/CAM design systems in your work. What are you trying to accomplish by combining these techniques?

Matthieu Cheminée: Being a teacher, I thought it was important to learn a CAD program. Today I am using it less and less; I like being at the bench way better. That being said, I think it is a great tool, and I still use it to make intricate bezels for oddly shaped stones or when I do pieces with writing. It is also great when clients want a piece that is totally different from what I normally like to do. I see CAD as a new technique, a new tool, and I always like to combine the new things I learn with what I do.

Your current exhibition at L. A. Pai Gallery in Ottawa is called Stampclastic. Tell us about the show and what “stampclastic” refers to. Is it a new technique?

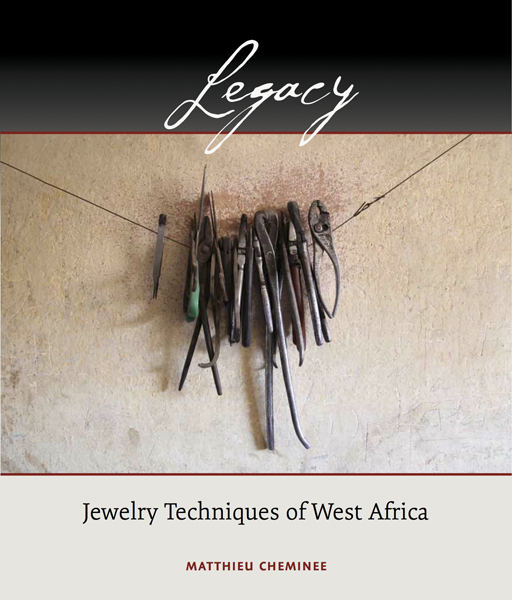

Matthieu Cheminée: I have been showing my work at L. A. Pai Gallery for more than 10 years. Lisa Pai has been a great support in my career, bringing some of my pieces to trade shows like SOFA. I love exhibiting there, so as soon as I told her about my book she offered to do a launch combined with a show of my latest pieces. The opening was a combination. I shared a talk on West African jewelers, showing their tools, their pieces, and their techniques as well.

I love the term “stampclastic.” It is a name I gave to the work I have been doing in the last two years. Every piece is made from a sheet of silver that has been fully stamped, creating patterns. Afterward, I cut a shape out of the sheet for bracelets or for rings and then, using a sinusoidal stake, I lightly anticlast them, giving them a more attractive shape as well as creating an amazing, comfortable fit. The name comes from these two techniques.

Matthieu Cheminée: After my stay in New Mexico I went to Mali, West Africa. A stay that was supposed to be a few weeks turned into a few years. Walking the streets of Bamako, I met many jewelers who welcomed me into their shops and their homes. They showed me technique after technique, never asking anything in return. When I moved to Canada I enrolled in a jewelry school to learn a more traditional approach to the trade. After a few years working as a jeweler and a teacher I went back to West Africa, this time to Guinea. Again I met jewelers who were more than generous. I started to film and photograph them at work to show my students back in Canada. Slowly I started offering conferences at the École de Joaillerie de Montréal, as well as workshops on the techniques in question. I am splitting the revenues of the workshops that I am offering with the jeweler who showed me the technique, and collecting tools and metal to bring on my next trip to give to jewelers. I have been doing that with more and more jewelers, from seven West African countries.

With the amazing help of my publisher, Tim McCreight, the whole project to help jewelers is taking a new turn. We have created a website called Toolbox Initiative, which allows any jeweler or individual to support jewelers in Africa by giving tools or metal. This is all possible thanks to great sponsors like Rio Grande.

Matthieu Cheminée: I would love to open a school in Guinea. My vision is to open a school that offers traditional techniques mixed with new ones, staffed by local teachers with a teacher from North America who would offer workshops. The school would be open not only for the traditional sons of jewelers but also for girls. And it would have a scholarship program for troubled youth. I have been talking about it for 10 years. I had meetings with government officials and jewelers. So far it is still in the same place. In the last few years, a coup and political instability have not helped, nor has the recent Ebola outbreak this year. For now Tim McCreight and I are planning to start with an existing jewelry school in Dakar, Senegal. Tim has been sending books and videos as well as tools that were given by students and teachers from the jewelry program of MECA in Portland, Maine.

How can the contemporary jewelry community contribute to your work in West Africa? Where can we buy a copy of your book?

Matthieu Cheminée: The response from the contemporary jewelry community has been great. The book, the iBook, and soon some videos will be a very good way to introduce these wonderful craftsmen to this part of the world. Some great artists and teachers such as Michael Good have already generously offered their help as teachers.

The toolbox initiative is a way to give and experience that feeling; it is from one jeweler to another. It is amazing to see the reaction of a jeweler when he receives a saw frame or a file. The person who offers a tool can see on the photo gallery to whom the tools were given.