The SMG aims to assemble an annual event with diverse programming to support the metals community across the Northwest. The Protective Ornament curator and current Metalsmith editor, Suzanne Ramljak, was the welcome keynote to this year’s lecture series. Ramljak’s opening presentation, All Is Fair in Love and War, provided groundwork for SMG to develop Metalsmithing as Continuum, “from ornament to armor,” “sculpture to furniture,” and “amulet to talisman” as thematic concepts for the day. The lecture series featured artist and fourth-generation jeweler Lori Talcott, art historian and curator of medieval art at the Cleveland Art Museum Stephen Fliegel, metalsmith Myra Mimlitsch-Gray, jeweler Todd Pownell, and sculptor Vivian Beer.

Seduction

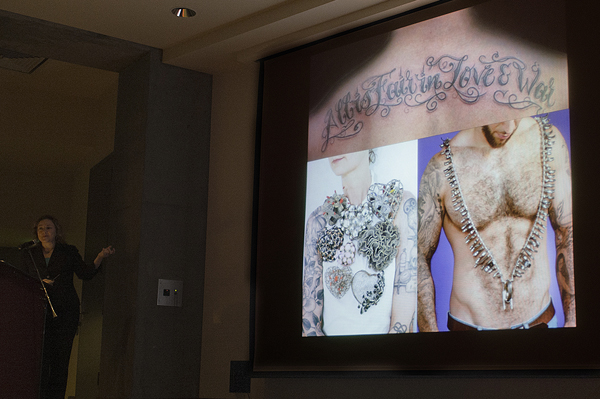

Not yet having seen the show, and given my limited knowledge of armor, I too felt apprehension as I anticipated a lecture filled with historically specific references. But Ramljak framed her research comfortably for a contemporary audience of makers and academics alike. Opening with an image of Boris Bally’s Brave 2 beside one of Lola Brooks wearing an assortment of her heart brooches, Ramljak made clear her focus on contemporary jewelry and ornament. Beginning with the concepts of love, seduction, and courtship and moving on to defense, she highlighted jewelry’s function as equipment for the innate human pursuits of love and war.

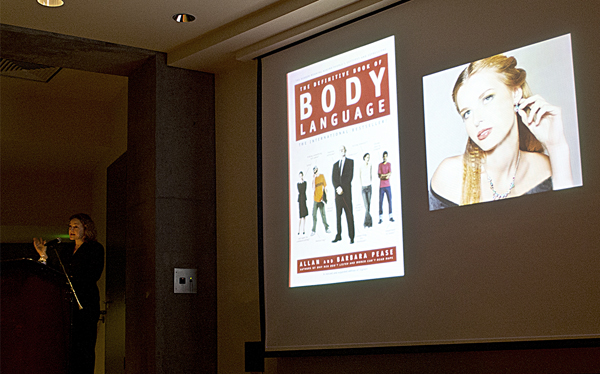

From Marilyn Monroe performing “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” to a glittering Tiffany ring, jewelry’s function as an agent of seduction is already well known in popular culture. Traditional jewelry has a long cultural history as a signifier of glamour, fame, wealth, courtship, and marriage. Ramljak tied strategies of seduction to contemporary jewelry objects and left the audience with a “few handy tips for seduction and survival.”

So what are the successful formal strategies of attraction and enticement that are active in contemporary jewelry and courtship? Ramljak described courtship as a process of mate selection—using Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection—and as a process within contemporary romantic relationships. The audience was given the following set of cues to think about: tension or a play of opposites, tactility/physicality, intimacy, and explicitness. From the tactile quality of Sun Kyoung Kim’s Interconnection series to the outspoken work of Keith Lewis, Ramljak revealed the connective thread between jewelry that previously may have felt wholly unrelated, and described each tenet’s place within courtship of a loved one; I couldn’t ignore (nor, I imagine, could the audience) obvious parallels with courting a contemporary jewelry buyer or collector.

When Love Meets War: Playing With People’s Minds

This phrase, “capture and disarm,” stuck in my mind for the rest of the day. In my own experiences in academia and beyond, decorative and ornamental objects are typically discussed based on the abilities and the authority of the maker. Ramljak’s research, however, highlights ornament’s authority independent of the strategies artists can employ when making work. Not only did this give the audience a new set of access points into the objects in Protective Ornament, but it also suggested a useful analytical perspective when approaching contemporary jewelry and other ornament.

Circling Round

Later that afternoon, metalsmith and educator Myra Mimlitsch-Gray stepped up to the podium and led the audience down an unexpected route through her 30 years of experience as an artist. Under the title circle:round, Mimlitsch-Gray discussed the history of her studio practice, framed by her choices to step away from the comforts of her bench and into residencies around the world.

Initially, Mimlitsch-Gray saw a residency as way to escape. Her first application was to the MacDowell Artist Colony, where the limited means and materials of the space challenged her expectations and required quick adaptation. Just like many other artists, she entered with a vision for a certain outcome. But the new space required an open mind and an improvisational working method she typically wouldn’t allow in her own workspace. She worked with cardboard, Xerox, stones, and copper flashing to create weapon forms and systems of display.

The challenge of a new space, community, tools, and materials repeated itself with each residency. Mimlitsch-Gray excitedly accepted each one of them as a chance to expand her artistic discourse while not coming back around to what she knew. She reflected that “history was like an albatross hanging around my neck (…) I was seeking to critique it and pay homage to it.”

Mimlitsch-Gray’s residency at the Kohler Co. brought her inside the factory, working alongside 300 male and seven female foundry employees. She describes her work Brat Pans and Modified Corn Pone Pan as the “blue collar, cast-iron version” of what she knew from her previous research. She also viewed cast iron as a material to reach a “broader audience, a factory audience.” This material and making process are unexpected from an artist very well known for her mastery of silversmithing and the raised form. Yet the attention to the history of the materials, the ode to the place of inspiration, and the craft within each piece make Mimlitsch-Gray’s mark very clear.

At the beginning of her presentation, Mimlitsch-Gray described her efforts to work on a set of familiar themes, objects, forms, ideas, and skills while consistently undermining her own efforts in the process. She described her efforts to strive toward mastery, while constantly thinking of “alternative strategies toward thinking and making in metal.” I found this idea remarkable for someone so highly regarded in metalsmithing. I believe this is part of what makes Mimlitsch-Gray’s work so engaging. Her objects come from an unrelenting process of discovery.

I was anticipating leaving circle:round with a background on Mimlitsch-Gray’s training and mastery. Having the opportunity to see photographs and hear reflections on her new and previously unseen work was exciting, but I was most interested to hear about the complexities behind her process. Reflecting on her time as a resident at Banff, MacDowell, the Kohler Co., and Konstfack, Mimlitsch-Gray’s discussion of each residency began to reveal how newness, discomfort, and forced adaptation can be key moments in an artist’s career. Much like school, a residency isn’t a guarantee of a life-changing body of work, but the skill and adaptation it demands can positively impact the growth of an artist’s process and vocabulary.

The lecture series continued until the end of the day with a range of presenters from unique backgrounds. Lori Talcott’s presentation, What would you take into the dark?, provided a glimpse into her jewelry’s relationship to history, tradition, and enchantment. Mirroring Suzanne Ramljak’s perspective, Talcott discussed how objects and things reflect and protect people’s emotional space and in turn, how people have always been dependent upon things for survival and companionship. Ramljak’s remarks on armor and amulets set the stage for Stephen Fliegel’s presentation, The Technology of Art: Arms & Armor of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Fliegel elaborated on how arms and armor are used for more than protection. Citing examples throughout history, he highlighted armor’s ability to embellish, establish authority, signify wealth, and establish patronage.

Ornament’s relationship with survival was key to the afternoon presentations. Each speaker disclosed jewelry and ornament’s role as a mechanism in the survival of his/her own artistic practice. Tod Pownell’s presentation, Live/Work—Finding Our Studio’s Stride, spoke of his transformation from a motorbike repairman to a jeweler committed to living his craft and maintaining an exhibition space to serve midcareer artists. The series closed with artist Vivian Beer presenting Practical and Preposterous Making. Beer discussed her work’ relationship to nature and culture, the importance of residencies and travel, and her vision that furniture’s ability to set a stage for bodies and intimacy runs parallel to the functions of jewelry.

Northwest

As the doors opened for the Protective Ornament reception at the Tacoma Art Museum, the 2014 Northwest Jewelry and Metals Symposium closed. According to many symposium veterans, this year’s program outshone many in the past. Protective Ornament, Suzanne Ramljak as the opening speaker, and the breadth of talks that followed left me believing that the moderately sized, regionally specific symposium was an event worth traveling to. If 2015 can match or surpass the scope of subject matter and include other nationally or internationally notable figures in the field, I will have the Northwest Symposium on my calendar again.

As the Seattle Metals Guild intended, the 2014 symposium offered a thoughtful set of programming for attendees. Suzanne Ramljak and Stephen Fliegel offered lectures that foregrounded scholarly research and balanced the otherwise maker-driven presentation series.

Unlike many of the symposia across the US that are grounded by relationships with academic communities or by a single thematic topic, the Northwest Symposium was established to serve a community inside a large geographical territory. Attendance was not exclusive to a well-defined region on a map. Makers, writers, teachers, scholars, and other attendees hailed from many neighboring states and Canada.

Protective Ornament came to Tacoma from its debut at the Metal Museum in Memphis, Tennessee. The draw of this nationally recognized traveling exhibition and the presentation from the curator undoubtedly contributed to the popularity of the symposium. Attendance nearly filled the auditorium, but the size and scope of the content kept the day intimate and accessible.

The Washington State History Museum space felt appropriately sized for the daylong event, but a venue that allowed for additional programming beyond an auditorium for presentations would be better suited to the symposium. There was an auction room along with the Charon Kransen book space, but in order to support the attendees as a community, the event would benefit from spaces for discussion or time off between lectures.

After attending the Zoom Symposium at Indiana University in 2013, I see the advantage of the Northwest Symposium adopting a similar multifaceted approach. A combination of a lecture series, a facilitated discussion space, and optional workshops would provide a more well-rounded and dynamic program. For a symposium that seeks to serve a large community, bringing in a wider variety of programming along with a lecture series of this year’s caliber would likely do more to serve the diversity of the jewelry and metals community across the Northwest.

INDEX IMAGES: Boris Bally, Brave 3: Necklace, 2013, 100 steel gun-triggers (courtesy Good4Guns Anti-violence Coalition, City of Pittsburgh, PA), stainless cord, 925 silver, 750 gold, 48,26 x 27,94 x 4,13 cm, photo: Aaron Usher III