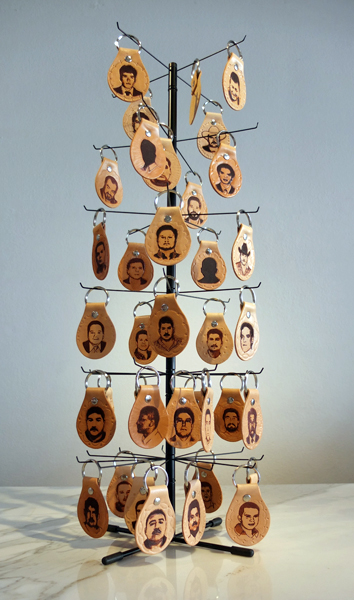

In the past week, I witnessed Che Guevara’s face on a hand-painted locker at my son’s middle school, stenciled on a derelict building, printed on a wine bottle label, and silkscreened on organic cotton onesies. Unmoored from its original context, Alberto Korda’s original black-and-white photograph of Che Guevara is obscured in a morass of commercialism: the idea of revolution reduced to a branding platform. It is in this kind of space, between the individual and the idea, that Greetings from Mexico or Souvenirs from the Border, 2013, by American self-described “materialsmith” Kerianne Quick, operates.

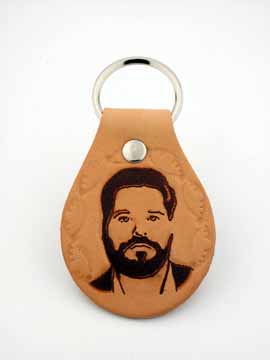

Shifting focus to reception from inception, the project begs consideration of who might purchase the work, and for what purpose. Pieces are sold individually, suggesting that some could be collected more than others. Would the fobs be perceived as relics of a revolutionary leader who protected a village, or as a head-on-a-stake of a terrorist who destroyed lives and disrupted international governmental systems? Would Cartel cameos be collected like baseball cards, with new project-specific value systems determined by criteria such as each man’s status as a fugitive, captured, or killed?

Located in the gallery or museum, the depth of Quick’s carefully researched project is masked by the work’s disarming casualness. Taken at “face value,” the project subverts multiple systems to which the artist responds, employing banal simplicity to entice visitor engagement. Abstracted from the original contexts of commerce, narrative content, borders, and the conflict itself, the work’s targeted audience is a specific category of cultural tourist: collectors. The project exemplifies the advantages of working in a privileged academic space where social commentary poses little risk of reprisal. Unlike Quick’s insertions in 2009, when she photographed her handmade leather purses with images of laboring women in stalls on the US side of the border, Greetings from Mexico is contingent on the safe haven of an art context.

Quick’s project is unquestionably timely and important. In February 2014, US and Mexican law enforcement officials captured Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, head of Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel, a man sought after for 13 years. Guzman is known for keeping the peace in Mazatlán and for stewing his enemies alive (see for example this article). Within the pristine preserve of the white cube, Guzman shifts from image to collectible object—but only sometimes between specter and person. Quick offers what she describes as a “glimpse of reality,” which is at its most effective in uncanny encounters with a man, woman, or child affected by the day-to-day realities of the Drug Wars. It is in these moments that the thinking and making behind the work are reified in a shift from social commentary to social engagement.

Greetings from Mexico is on view at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft until September 7, 2014, as part of La Frontera exhibition.