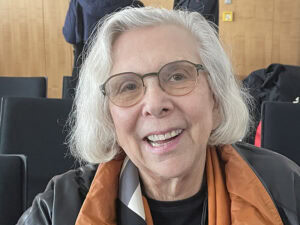

Last October 2012, at the time of the opening of the Rita J and Stanley H Kaplan Family Foundation Gallery at the Boston MFA, I had the opportunity to sit down and talk with Yvonne Markowitz, the museum’s curator of jewelry. (You can read a review of the Kaplan gallery’s first exhibition, Jewels, Gems, and Treasures: Ancient to Modern, on the AJF website.) Markowitz, who has been at the museum for over two decades, became the Rita J Kaplan and Susan B Kaplan Curator of Jewelry in 2006. She presides over more than 11,000 items of jewelry in the MFA collection, spanning what seems like all the times and places where jewelry or adornment has been made and worn. We discussed ancient and modern jewelry, the place of contemporary jewelry in the museum, as well as the process of acquisitions and Markowitz’s plans for the future.

Damian Skinner: Tell me about your position at the museum.

Yvonne Markowitz: I started out at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, as an Egyptologist, that’s my background and I spent eighteen years in what was originally the Egyptian department but is now the Art of the Ancient World and my specialty in that department was ancient jewelry. I did Egypt, Nubia, ancient Near East and ventured a little bit into Greco-Roman jewelry. We have very important ancient Egyptian and Nubian jewelry because the museum and Harvard University excavated for several decades in both Egypt and Nubia, which is now Sudan, and the situation then was that there was a 50/50 divide, 50 percent of the objects stayed in either Cairo or Khartoum and the other 50 percent came to Boston. So we were able to build a wonderful collection of ancient jewelry and particularly important ancient Egyptian beadwork. My first move forward in time was nineteenth century revivalist jewelry, which was based on ancient excavated material. That opened up the door to the nineteenth century for me. At the time there really wasn’t much of an interest in jewelry in the museum, so I had pretty much free rein going through storage areas and getting a sense of the collection as a whole.

Then, in 2006, one of our trustees met with me and said jewelry had been the passion of her and her mother and they were avid collectors and they were interested in endowing a curatorship dedicated to jewelry. We talked briefly about that – for me, it meant going forward a couple of thousand years in time and although I had been playing around in the collection, I knew I was going to have to do a lot of catch-up. I realize now it’s easier going forward than going backward, because a lot of ancient jewelry has text on it and if you don’t have an understanding of those languages and cultures you’re never going to get it. Anyway, one of my tasks early on was to learn about those other two thousand years.

How did you do that?

I worked really hard and I was directed toward certain collectors that were museum friends already and others I had known through my jewelry associations prior to taking on the new role. One was a private collecting couple in Philadelphia and they had probably the best collection of art nouveau jewelry in private hands in America. We did an exhibition of that collection here at the museum and I worked on that for a couple of years, meanwhile plugging away, acquiring other pieces and learning along the way. The last five years have been very much learning years for me and building on what I knew before. I have a very receptive director, I don’t know how many directors of fine arts museums in the United States are very interested in jewelry but Malcolm Rogers is. He was extremely supportive, especially as I tried to make assessments of what our strengths and weaknesses were, trying to enhance the strengths and filling in some holes. We’ve made some wonderful acquisitions, probably between 300 and 400 acquisitions.

What’s your formal title?

I am the Rita J Kaplan and Susan B Kaplan Curator of Jewelry. This is the mother and daughter I told you about. The Kaplan family foundation has also endowed a gallery that is dedicated to jewelry and will have rotating exhibitions every two to three years. The first one is Jewels, Gems and Treasures: Ancient to Modern and it draws a lot on our permanent collection with some loans.

How do you fit in to the larger structure of the museum?

The first thing I did was move out of the Art of the Ancient World and into the Department of Textile and Fashion Arts. It really wouldn’t make much difference which department I was in, but this just seemed to be a good fit because of their encyclopedic approach to textiles. And there is a close relationship between jewelry and dress, that’s another tie in.

The collections you deal with, how are they located within the museum?

Since I came on board, every piece of jewelry comes into this department. Otherwise, jewelry resides in the storage area of their respective departments. For example, the Daphne Farago collection, which came in right before I started as Curator of Jewelry, entered the Art of the Americas because it’s about 70 percent American, 30 percent European. Our Asiatic department has Asian jewelry in their storerooms, the Art of the Ancient World has ancient jewelry and so on.

Probably every department in the museum has some connection to jewelry. For example, Prints, Drawings & Photography has fashion photography showing women wearing fabulous jewels, as well as prints of jewelry designs and that’s just one department. The curator of African art in the African and Oceania department has a strong interest in African beadwork and has made some wonderful acquisitions. Art of the Americas has hollowware and some jewelry by Paul Revere and other Americans. When I first joined the museum the departments were pretty much isolated islands, but over the last ten years there has been an enormous amount of inter-departmental activity. For example, the curator of contemporary craft said to me, if you see a wonderful contemporary studio piece let me know and vice versa. It is very collegial and inter-departmental and I think that’s probably quite different from most other museums.

It is interesting that jewelry in the ancient world has always been integrated into the collection. You’ll see that there is jewelry next to ceramics next to glass next to sculpture, because that’s the way that scholars of ancient art think of it. Traditionally, that didn’t happen in the art of Europe and the art of America, but it does now in this museum, that’s the model that we used. If you have the opportunity to go and see the new American wing, the third floor, which deals with the twentieth century, you’ll see that there are about 25 pieces of jewelry from the Farago collection on view. There would have been more but the American wing stops at 1960, as that’s where the contemporary galleries take up the story. And if you go to the contemporary galleries, which opened in September 2011, you’ll find more jewelry on display.

How do you deal with being responsible for jewelry from all times and places?

People, including me, come with their strengths and weaknesses. An area where I really need to develop myself more would be the ancient Americas. If you have a good background in the classics, Europe and America come easily. It’s these other cultural entities that are tougher because, again, you have to have an understanding of the culture. For example, I’ve just finished a book on the highlights of the museum collection and there was this wonderful Korean sutra case, in which you’d keep scriptures or text. You open up the case and inside are six Sanskrit letters, characters in circular surrounds. I don’t read Sanskrit, but I have the resource here to go to somebody and say tell me what this is about. That’s the advantage of being in an encyclopedic museum. And if there’s no one here, Boston and Harvard University are right here. We are not lacking in resources. I find, too, that people who are interested in jewelry in United States are very collegial and willing to share information.

Do you have an acquisitions budget for purchases?

There are no specially endowed funds for jewelry. There’s a special fund here for coins and medallions. And then there are general funds, so you have to make your pitch to the museum’s Collections Committee. Right now we are in the process of acquired a pendant/brooch featuring an enameled image of the Classical Goddess of Dawn (Aurora) driving a chariot. It dates to around 1885 and was made by the American firm, Jacques & Marcus – it would later become Marcus & Co.

Tell me how the acquisition process works.

What I first do is research the piece and make sure I’ve made the case well to myself. Then I speak to my department head and then I go to the director of the museum. There is a group of trustees that form what we call our Collections Committee and I make a presentation in front of the Collections Committee. This process involves an informal aspect, conversations, showing things to people, as well as a more formal presentation. The committee votes on whether or not to acquire the object.

And is the committee receptive to your requests?

I have not been denied anything. But again there are small steps along the way. One thing is if something has been donated or a donor steps up to the plate and says I’ll buy that for you, as opposed to competing with all the other curators for certain general funds. All those things are taken into consideration.

Tell me how contemporary jewelry fits into the larger jewelry stories that you are presenting in the museum.

You would consider contemporary jewelry to be from the 1940s onwards? You don’t include American arts and crafts jewelry from the early twentieth century in that term?

No. I would probably say it starts with modernist jewelry.

Okay, because the underpinnings of the philosophy are there early on.

That earlier moment is never written into the histories, even though I agree with you that it is very similar in its intentions and ideas of morality and artistic expression and so on.

In my mind it is a thread interrupted by art deco and retro. The Farago collection is about 650 pieces of studio jewelry, 70 percent American, 30 percent European and the rest of the world. The collector, Daphne Farago, very early on decided it was to be a museum collection, and she worked very well with dealers and curators with the idea that for any given artist who she thought was important, she wanted the best piece they’d ever done – and she had people help her seek those pieces out. So the collection in terms of caliber is very fine. It differs from the Helen Drutt collection now in the Houston Museum of Fine Art in that Daphne was very interested in the early decades of the movement and really honed in on getting a good foundation there, so that’s now a great strength of our collection. The Farago collection added to a core of 100 pieces, mostly American, which we had collected in the 1980s and 1990s. There was an Art Smith bracelet, for example, but nothing like the two Art Smith necklaces that we have now. What Daphne collected was just the best, so we have now probably about 750 pieces.

Of contemporary jewelry?

Yes.

And how many piece of jewelry in the collection?

About 11,000.

How would that break down? What are your strongest areas in the collection?

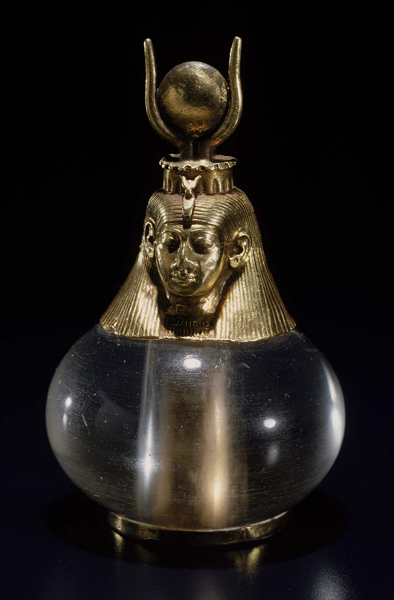

Egypt and Nubia would have to be at the top. We have the best Nubian collection of jewels in the world, because the excavator who worked in Egypt – his name is George Andrew Reisner – began looking south when the French, Germans and Italians became established in Egypt. He knew that there were some wonderful pyramid cemeteries modeled on the Egyptian ones that had been plundered to a certain extent in antiquity but were otherwise pristine and so he was able to get licenses for those excavations. Some were royal tombs, so we have some wonderful, beautiful royal jewels. Probably in terms of numbers of the jewelry from Nubia, it’s around 800 pieces I would say.

Then we have some wonderful purchased and donated Grecian-Roman jewelry, an exceptional collection of Middle Eastern cylinder seals, and extraordinary classical engraved cameos and gems, including a number from the Marlborough collection, a very famous English collection of gems. There are also some outstanding Byzantine adornments. We would like to add to our medieval jewelry holdings – the same with the Renaissance. We have a very strong collection of arts and crafts jewelry, particularly Boston-related. Because the American department has such an extensive hollowware collection of silversmiths from New England, it was natural for them to go one step further and look at metal working in jewelry. As a result, we do have some really fine early examples from the colonial period of clasps and shoe buckles, mourning jewelry, that sort of thing from New England in particular. And then for Asiatic jewelry, there was a late nineteenth/early twentieth century collector, his name is Denman Ross, who lived a few years in India and acquired some gem-set Moghul jewels and we have some interesting ethnic jewels from North Africa, some Islamic pieces. It’s pretty comprehensive, but in terms of stellar pieces, it’s these little pockets.

At any point, how many of the 11,000 objects would be on display?

A fairly small percent. I’d say right now ancient jewelry has the most jewelry on view. For the Americas there’s a nice selection of Farago pieces up and an abundance of ancient American pieces, both in jade and gold. That’s on the first level of the new wing – that’s another strength of ours also, gold from ancient Americas.

What jewelry-related projects are coming up?

The Farago book was just published and two years ago we published Imperishable Beauty: Art Nouveau Jewelry. I have just finished the book about highlights from the jewelry collection, called Artful Adornments, which is connected to the first exhibition in the Kaplan gallery. That includes a chapter called ‘Jewelry Avant Garde’, which actually starts with the British Arts and Crafts movement and goes through to studio jewelry. I am currently working on a book on the American high-style jewelry firm, Trabert & Hoeffer – Mauboussin (1936-53). When that’s completed, I will begin a book on Nubian jewelry with colleague Denise Doxey from the Art of the Ancient World Department.

What’s the next exhibition in the dedicated jewelry gallery?

Nubian jewelry. It will draw on the museum’s extensive collection of this material which has largely been in storage for the last half-decade.

How do you deal with being responsible for jewelry of all times and places? How do you create a coherent practice, given the massive differences?

I would be the person who gets it together. For example, I’ve recently talked with a couple of the ancient curators about doing an exhibition of ancient jewelry along with all the nineteenth century revivals, from micro-mosaics to granulation, all of that, including modern jewelers like John Paul Miller or Margret Craver who used these processes, just talking techniques. The strange thing is that all of these techniques seem to be rediscovered in their own time without people really understanding all they had to do was visit a museum like this one. Poor John Paul Miller told me all the grief he had experimenting with granulation. In the early 1920s there was an Egyptologist named Caroline Ransom Williams who worked with a Columbia University scientist, and together they published a paper on how the ancient Egyptians granulated precious metals.

I suppose it is difficult to know where such information exists. I was thinking the other day about amulets and talismans as they relate to contemporary jewelry. There must be a significant amount of anthropological and archaeological material on this subject, but unless you know the discipline, it is difficult to access this information and draw on the lessons in your own work.

The advantage that studio jewelers have is that many of them have educations that are university based and they know that if they need to make certain contacts, they can go to someone who’s a specialist in a certain area. I don’t think that was so true in the 1950s but it certainly is now. If someone like Mary Lee Hu or Jan Yeager’s really interested in finding something out, she’s going to know what telephone calls to make. Much of the early studio jewelry is . . . I don’t want to use the word crude, but you find a lot of examples like Calder, he’s twisting wires, he doesn’t even solder, its pretty elemental. But now you get someone like Linda McNeil, her glass is incredibly sophisticated, she works with optical glass, she’s in contact with folks at the Corning Glass Museum, it’s at a level of sophistication that is very different to most mid-twentieth century jewelers.

Do you have a favorite period of jewelry?

It would probably be ancient Nubia.

Why?

They’re a country very influenced by Egypt, but they had their own take on what they borrowed. I admire that little originality which makes them unique, especially as they could easily have been totally dominated in terms of iconography and even materials. We’re talking about 750BC to 300AD and these are individuals, craftsmen who can do the full range of almost every enamel technique. So this is a culture where they are experimenting and working at an extremely high level, but it has all the Egyptian figures and science and gods that I’m fond of. It’s an amalgam and I’ve worked with it for so long. I’ve always felt the obligation because we have the most important jewelry holdings from Nubia and we have all the excavation records, so it’s really our obligation. Nubian jewelry will be a future book.

Damian Skinner: Tell me about your position at the museum.

Yvonne Markowitz: I started out at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, as an Egyptologist, that’s my background and I spent eighteen years in what was originally the Egyptian department but is now the Art of the Ancient World and my specialty in that department was ancient jewelry. I did Egypt, Nubia, ancient Near East and ventured a little bit into Greco-Roman jewelry. We have very important ancient Egyptian and Nubian jewelry because the museum and Harvard University excavated for several decades in both Egypt and Nubia, which is now Sudan, and the situation then was that there was a 50/50 divide, 50 percent of the objects stayed in either Cairo or Khartoum and the other 50 percent came to Boston. So we were able to build a wonderful collection of ancient jewelry and particularly important ancient Egyptian beadwork. My first move forward in time was nineteenth century revivalist jewelry, which was based on ancient excavated material. That opened up the door to the nineteenth century for me. At the time there really wasn’t much of an interest in jewelry in the museum, so I had pretty much free rein going through storage areas and getting a sense of the collection as a whole.

Then, in 2006, one of our trustees met with me and said jewelry had been the passion of her and her mother and they were avid collectors and they were interested in endowing a curatorship dedicated to jewelry. We talked briefly about that – for me, it meant going forward a couple of thousand years in time and although I had been playing around in the collection, I knew I was going to have to do a lot of catch-up. I realize now it’s easier going forward than going backward, because a lot of ancient jewelry has text on it and if you don’t have an understanding of those languages and cultures you’re never going to get it. Anyway, one of my tasks early on was to learn about those other two thousand years.

I worked really hard and I was directed toward certain collectors that were museum friends already and others I had known through my jewelry associations prior to taking on the new role. One was a private collecting couple in Philadelphia and they had probably the best collection of art nouveau jewelry in private hands in America. We did an exhibition of that collection here at the museum and I worked on that for a couple of years, meanwhile plugging away, acquiring other pieces and learning along the way. The last five years have been very much learning years for me and building on what I knew before. I have a very receptive director, I don’t know how many directors of fine arts museums in the United States are very interested in jewelry but Malcolm Rogers is. He was extremely supportive, especially as I tried to make assessments of what our strengths and weaknesses were, trying to enhance the strengths and filling in some holes. We’ve made some wonderful acquisitions, probably between 300 and 400 acquisitions.

What’s your formal title?

I am the Rita J Kaplan and Susan B Kaplan Curator of Jewelry. This is the mother and daughter I told you about. The Kaplan family foundation has also endowed a gallery that is dedicated to jewelry and will have rotating exhibitions every two to three years. The first one is Jewels, Gems and Treasures: Ancient to Modern and it draws a lot on our permanent collection with some loans.

How do you fit in to the larger structure of the museum?

The first thing I did was move out of the Art of the Ancient World and into the Department of Textile and Fashion Arts. It really wouldn’t make much difference which department I was in, but this just seemed to be a good fit because of their encyclopedic approach to textiles. And there is a close relationship between jewelry and dress, that’s another tie in.

Since I came on board, every piece of jewelry comes into this department. Otherwise, jewelry resides in the storage area of their respective departments. For example, the Daphne Farago collection, which came in right before I started as Curator of Jewelry, entered the Art of the Americas because it’s about 70 percent American, 30 percent European. Our Asiatic department has Asian jewelry in their storerooms, the Art of the Ancient World has ancient jewelry and so on.

Probably every department in the museum has some connection to jewelry. For example, Prints, Drawings & Photography has fashion photography showing women wearing fabulous jewels, as well as prints of jewelry designs and that’s just one department. The curator of African art in the African and Oceania department has a strong interest in African beadwork and has made some wonderful acquisitions. Art of the Americas has hollowware and some jewelry by Paul Revere and other Americans. When I first joined the museum the departments were pretty much isolated islands, but over the last ten years there has been an enormous amount of inter-departmental activity. For example, the curator of contemporary craft said to me, if you see a wonderful contemporary studio piece let me know and vice versa. It is very collegial and inter-departmental and I think that’s probably quite different from most other museums.

It is interesting that jewelry in the ancient world has always been integrated into the collection. You’ll see that there is jewelry next to ceramics next to glass next to sculpture, because that’s the way that scholars of ancient art think of it. Traditionally, that didn’t happen in the art of Europe and the art of America, but it does now in this museum, that’s the model that we used. If you have the opportunity to go and see the new American wing, the third floor, which deals with the twentieth century, you’ll see that there are about 25 pieces of jewelry from the Farago collection on view. There would have been more but the American wing stops at 1960, as that’s where the contemporary galleries take up the story. And if you go to the contemporary galleries, which opened in September 2011, you’ll find more jewelry on display.

People, including me, come with their strengths and weaknesses. An area where I really need to develop myself more would be the ancient Americas. If you have a good background in the classics, Europe and America come easily. It’s these other cultural entities that are tougher because, again, you have to have an understanding of the culture. For example, I’ve just finished a book on the highlights of the museum collection and there was this wonderful Korean sutra case, in which you’d keep scriptures or text. You open up the case and inside are six Sanskrit letters, characters in circular surrounds. I don’t read Sanskrit, but I have the resource here to go to somebody and say tell me what this is about. That’s the advantage of being in an encyclopedic museum. And if there’s no one here, Boston and Harvard University are right here. We are not lacking in resources. I find, too, that people who are interested in jewelry in United States are very collegial and willing to share information.

Do you have an acquisitions budget for purchases?

There are no specially endowed funds for jewelry. There’s a special fund here for coins and medallions. And then there are general funds, so you have to make your pitch to the museum’s Collections Committee. Right now we are in the process of acquired a pendant/brooch featuring an enameled image of the Classical Goddess of Dawn (Aurora) driving a chariot. It dates to around 1885 and was made by the American firm, Jacques & Marcus – it would later become Marcus & Co.

Tell me how the acquisition process works.

What I first do is research the piece and make sure I’ve made the case well to myself. Then I speak to my department head and then I go to the director of the museum. There is a group of trustees that form what we call our Collections Committee and I make a presentation in front of the Collections Committee. This process involves an informal aspect, conversations, showing things to people, as well as a more formal presentation. The committee votes on whether or not to acquire the object.

I have not been denied anything. But again there are small steps along the way. One thing is if something has been donated or a donor steps up to the plate and says I’ll buy that for you, as opposed to competing with all the other curators for certain general funds. All those things are taken into consideration.

Tell me how contemporary jewelry fits into the larger jewelry stories that you are presenting in the museum.

You would consider contemporary jewelry to be from the 1940s onwards? You don’t include American arts and crafts jewelry from the early twentieth century in that term?

No. I would probably say it starts with modernist jewelry.

Okay, because the underpinnings of the philosophy are there early on.

That earlier moment is never written into the histories, even though I agree with you that it is very similar in its intentions and ideas of morality and artistic expression and so on.

In my mind it is a thread interrupted by art deco and retro. The Farago collection is about 650 pieces of studio jewelry, 70 percent American, 30 percent European and the rest of the world. The collector, Daphne Farago, very early on decided it was to be a museum collection, and she worked very well with dealers and curators with the idea that for any given artist who she thought was important, she wanted the best piece they’d ever done – and she had people help her seek those pieces out. So the collection in terms of caliber is very fine. It differs from the Helen Drutt collection now in the Houston Museum of Fine Art in that Daphne was very interested in the early decades of the movement and really honed in on getting a good foundation there, so that’s now a great strength of our collection. The Farago collection added to a core of 100 pieces, mostly American, which we had collected in the 1980s and 1990s. There was an Art Smith bracelet, for example, but nothing like the two Art Smith necklaces that we have now. What Daphne collected was just the best, so we have now probably about 750 pieces.

Yes.

And how many piece of jewelry in the collection?

About 11,000.

How would that break down? What are your strongest areas in the collection?

Egypt and Nubia would have to be at the top. We have the best Nubian collection of jewels in the world, because the excavator who worked in Egypt – his name is George Andrew Reisner – began looking south when the French, Germans and Italians became established in Egypt. He knew that there were some wonderful pyramid cemeteries modeled on the Egyptian ones that had been plundered to a certain extent in antiquity but were otherwise pristine and so he was able to get licenses for those excavations. Some were royal tombs, so we have some wonderful, beautiful royal jewels. Probably in terms of numbers of the jewelry from Nubia, it’s around 800 pieces I would say.

At any point, how many of the 11,000 objects would be on display?

A fairly small percent. I’d say right now ancient jewelry has the most jewelry on view. For the Americas there’s a nice selection of Farago pieces up and an abundance of ancient American pieces, both in jade and gold. That’s on the first level of the new wing – that’s another strength of ours also, gold from ancient Americas.

What jewelry-related projects are coming up?

The Farago book was just published and two years ago we published Imperishable Beauty: Art Nouveau Jewelry. I have just finished the book about highlights from the jewelry collection, called Artful Adornments, which is connected to the first exhibition in the Kaplan gallery. That includes a chapter called ‘Jewelry Avant Garde’, which actually starts with the British Arts and Crafts movement and goes through to studio jewelry. I am currently working on a book on the American high-style jewelry firm, Trabert & Hoeffer – Mauboussin (1936-53). When that’s completed, I will begin a book on Nubian jewelry with colleague Denise Doxey from the Art of the Ancient World Department.

What’s the next exhibition in the dedicated jewelry gallery?

Nubian jewelry. It will draw on the museum’s extensive collection of this material which has largely been in storage for the last half-decade.

How do you deal with being responsible for jewelry of all times and places? How do you create a coherent practice, given the massive differences?

I would be the person who gets it together. For example, I’ve recently talked with a couple of the ancient curators about doing an exhibition of ancient jewelry along with all the nineteenth century revivals, from micro-mosaics to granulation, all of that, including modern jewelers like John Paul Miller or Margret Craver who used these processes, just talking techniques. The strange thing is that all of these techniques seem to be rediscovered in their own time without people really understanding all they had to do was visit a museum like this one. Poor John Paul Miller told me all the grief he had experimenting with granulation. In the early 1920s there was an Egyptologist named Caroline Ransom Williams who worked with a Columbia University scientist, and together they published a paper on how the ancient Egyptians granulated precious metals.

The advantage that studio jewelers have is that many of them have educations that are university based and they know that if they need to make certain contacts, they can go to someone who’s a specialist in a certain area. I don’t think that was so true in the 1950s but it certainly is now. If someone like Mary Lee Hu or Jan Yeager’s really interested in finding something out, she’s going to know what telephone calls to make. Much of the early studio jewelry is . . . I don’t want to use the word crude, but you find a lot of examples like Calder, he’s twisting wires, he doesn’t even solder, its pretty elemental. But now you get someone like Linda McNeil, her glass is incredibly sophisticated, she works with optical glass, she’s in contact with folks at the Corning Glass Museum, it’s at a level of sophistication that is very different to most mid-twentieth century jewelers.

Do you have a favorite period of jewelry?

It would probably be ancient Nubia.

Why?

They’re a country very influenced by Egypt, but they had their own take on what they borrowed. I admire that little originality which makes them unique, especially as they could easily have been totally dominated in terms of iconography and even materials. We’re talking about 750BC to 300AD and these are individuals, craftsmen who can do the full range of almost every enamel technique. So this is a culture where they are experimenting and working at an extremely high level, but it has all the Egyptian figures and science and gods that I’m fond of. It’s an amalgam and I’ve worked with it for so long. I’ve always felt the obligation because we have the most important jewelry holdings from Nubia and we have all the excavation records, so it’s really our obligation. Nubian jewelry will be a future book.