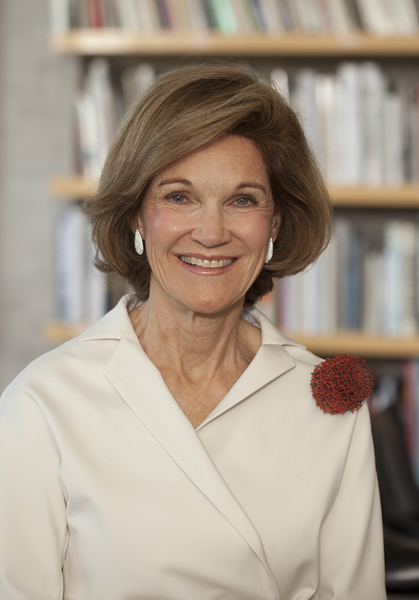

Susan Cummins: Deedie, I understand that you’re part of a group of collectors that are coordinating efforts to build a strong contemporary art collection for the Dallas Museum of Art. Can you describe how that got started and how that works?

Deedie Rose: Yes. Three couples—Cindy and Howard Rachofsky, Marguerite and her late husband Robert Hoffman, and my husband and I—all irrevocably bequeathed our collections of contemporary art to the Dallas Museum of Art. We are all close friends and we have been involved for a long time at the Dallas Museum of Art. I think we all believe that art is transformative—that it can change your life, and that it’s certainly a way of lifelong learning. Because it’s so important in our lives, we wanted everybody to have access to it. We want our museum to be a great one, and this was part of that effort. Since we did that, other people have joined us, and that was the hope—to get people thinking that maybe they are just caretakers of their art and that they might ultimately give it to the DMA and to the public.

It’s been about the most rewarding thing I have ever done. Also the most selfish because now I can buy something and rationalize that it isn’t really for me. It is for the museum. So I can’t say that it’s been completely altruistic. It’s just been a rationalization on my part for buying something that I love and would like to live with for a while.

Deedie Rose: If I am gifting it right then, it has to be passed through a collections committee and voted on. If I am buying it for myself, which is usually the case, then we don’t need to go through those steps.

I’ve also bought pieces with Howard and Cindy, [or] with Marguerite, because we all think we can buy more if we buy with each other. In reality, we’re spending the same amount of money or more. We kind of egg each other on. I don’t usually consult with a curator, but I do have a wonderful art consultant who has become one of my best friends. He’s just a great guy. He’s Howard’s consultant, too, which helps us coordinate. We try to not overlap in the things we’re buying. I collect more in the Latin America area. Marguerite is more interested in modern masters. And Howard collects edgier things, really “out there” art. But together, I think we’re helping the museum form a collection that can tell many stories.

When did you realize that jewelry might be a collectible item, and what kind of jewelry are you collecting?

Deedie Rose: As has been true so many times, I didn’t consciously choose. I didn’t start out thinking, “I am going to collect studio artists’ jewelry.” Twenty or so years ago I was reading a Metropolis Magazine and saw a picture of two pieces of jewelry made of stainless steel. They were geometric, very simple, rather stark, and large, and I loved them. The designer was a woman named Eva Eisler and I wondered how I would find her. This was pre-Internet so I called the magazine—found out that she lived in New York. I found a number in the phone book, called her, and told her I had seen a piece in that magazine and asked if she ever sold anything, and she said, “Well, yes.”

When I went to her apartment I was just fascinated with what she did. She said, “Well, if you like my jewelry, I think you would also like a friend of mine, Pavel Opocensky. He’s carried by a gallery in Washington, DC, called Jewelers’Werk,” and that was my real entry into this world.

Deedie Rose: At first I bought pieces that I loved and wanted to wear. I was also fascinated with the ideas behind them. The next time I went to Washington, DC, I went to Jewelers’Werk. I don’t think Ellen Reiben was there that day. It was her old space and it was the size of that sofa, probably. It was so tiny but it was filled with things that I just couldn’t believe.

I couldn’t imagine that things made to adorn the body were made with these types of materials or done in this fashion. It was so thrilling to me and so mind-blowing, which is what I love about art also. It’s showing you new ways of thinking, and that jewelry made me think in new ways.

That was when I really became acquisitive with the jewelry. I wanted it to wear, and that’s another one of your questions. Absolutely, I wear, though not everything. There are some things that are either too fragile or that I just haven’t figured out yet exactly how to wear it, because I want to look good. I don’t want to look just crazy, although I don’t mind looking slightly crazy because people think I am anyway.

So when did you think about working with the museum?

Deedie Rose: The curator of decorative arts at the DMA is Kevin Tucker, and I like Kevin a lot. I sat next to him at a lunch one day and I was wearing some great cuffs that I had found in New York. I asked if he would ever think of doing a little exhibition with some of this jewelry.

And that was the beginning. The DMA didn’t have a collection of contemporary jewelry. But it did have jewelry in the early Greek and Mayan collections. So there is a precedent for things that [adorn the body], and that’s when we started thinking about forming a collection for the museum. I talked to Ellen about it because Ellen has been my conduit. She is now such a good friend and has opened this world for me. Kevin and the director of the museum and I made a trip to Washington together, and we were like kids in a candy shop.

A lot of the things that we bought on that trip, I went ahead and gifted immediately. Two pieces were by Sergey Jivetin. People often ask, “What’s your favorite?” And I always say, “I don’t have a favorite.” But, I really, really love Sergey Jivetin.

Which piece of his did you get, or did you get several?

Deedie Rose: I have several now. The two pieces that I bought right then were clearly not for a person to wear. One was a very long tube of flexible clear plastic, and inside were all the little tools that a jeweler uses to make jewelry, and it wound all over the table. It’s a great display piece to bring people in and make them curious. Had you worn it as jewelry, you would have wrapped it around and around as a necklace.

I’ve never even seen that piece. It sounds amazing.

Deedie Rose: It is an amazing thing. And then another piece was a brooch made of little watch hands, very delicate. But most of the jewelry I have kept and I wear as much as I can because when other people see you wearing it, perhaps with a beautiful gown at a museum event, they wonder about it. They definitely don’t overlook it.

Do you ever disagree with what Kevin is choosing when you’re on a trip like that?

Deedie Rose: Kevin would probably like for me to buy more mid-century modern because he knows that material so well. I tend to like very contemporary work. I’m not as interested in pieces of jewelry made by artists whose main art form is not jewelry.

Deedie Rose: However I do have a great piece by Louise Bourgeois.

The necklace?

Deedie Rose: The necklace, yes.

Now, that’s a strong piece.

Deedie Rose: That is a strong piece.

And somebody made that. You can see the mark of the making on it. I’d like to see yours just to see if it has that mark because mine looks like somebody cranked along trying to get that big thick piece of silver to bend, and so you can really see the making of it.

Deedie Rose: And that is her, too, that toughness that is for a feminine person … I love that piece. So that was a piece by an artist whose main medium is something else, but that was real jewelry. That wasn’t just made as a commercial thing to sell. I struggled with that for a while, “What is this stuff that I’m collecting, and what do you even call it?” Really, I didn’t know what to call it until I read the Daphne Farago book, and it referred to “studio artists.” I thought, “Oh, that’s the category.” But how long had I been doing this and I didn’t even know what to call it?

People still don’t really know. People call it all kinds of things: author jewelry, art jewelry, contemporary jewelry. None of which truly describes studio jewelry, and in some ways describes it best because if you just call it “art jewelry” or “artist jewelry,” then you’re back into the, “Is it by an artist?” Yes, it is, but not an artist who uses other materials. So it still is confusing. One of the problems with the field is that it doesn’t know what to call itself.

Deedie Rose: For me, that term is the most descriptive and it usually indicates that that person is making it themselves. When I say, “I collect jewelry. We’re starting a jewelry collection,” most people think I mean a big diamond ring, or beautiful huge pearls.

Deedie Rose: They’re making it themselves.

Right, and, “It’s a particularly fascinating area of expression and not many people know much about it, but that’s what I’m collecting.” But the picture that people conjure up is hard to change by talking, unfortunately.

Deedie Rose: Right, it really is. And that’s going to be part of the task for me just because I care about it. I think this kind of jewelry is an entry into the world of the visual arts where you learn things and you’re opened up to new ideas. This is just one other way to do it, but it’s hard with little, tiny things for the man on the street to know why that would be interesting to him. And that’s, to me, the real nut we have to crack with the museum, and that’s part of what I want to ask you about as we talk today—installations that you’ve seen that made you say, “Wow, I have to tell everyone to go see that.”

Well, you have to like the intimate. You have to like the miniature, the small scale.

Deedie Rose: Yes and museums are often about big, big spaces. We worked with one firm out of Paris called Projectiles on the Jean Paul Gaultier fashion exhibition, and they made me think they would be able to design a fascinating installation for small objects.

That was a great show that came to San Francisco, too, unbelievably great, really.

Deedie Rose: It did what a great art exhibition should do.

It absolutely did. I mean, it is my example of a great, involving, completely “wow” type of exhibition that anybody can get interested in.

Kevin and I have talked to the Projectiles designers—what brains they have!—they are just so “out there.” That’s the kind of brain to do an installation for the museum jewelry. I’m not smart enough or creative enough to figure out what it is, but I think they might be.

It’s so important you’re thinking about this.

Deedie Rose: Now I want to tell you about another lovely thing that has happened, seemingly just “out of the blue.” A year and a half ago, Rusty and I were travelling with a group of friends to Vienna. Our plane was delayed and we got in late to Vienna, making us late to meet a man named Paul Asenbaum and to see the Wiener Werkstätte furniture that he deals in.

Paul, a most knowledgeable and wonderful man, had to give us a slightly hurried tour through the exquisite things in his gallery. At the end of our visit, I said something that made him realize that I was interested in contemporary jewelry, and he said that his mother, Inge Asenbaum, also had been. When I asked about the artists she had collected, he took us into his storage area, and started opening drawer after drawer—literally taking my breath away.

What started as a late, slightly reluctant visit to someone whose name I hadn’t previously known continued into conversations over the following year, and has now resulted in the beautiful collection of Inge Asenbaum arriving in Dallas, as an acquisition that will ultimately benefit the Dallas Museum of Art.

And you did it. So now the Dallas Museum of Art has a very large and important jewelry collection from Inge Asenbaum. What a fantastic contribution to the museum collections in the United States. By purchasing this collection as a whole you have raised the bar for all other collectors to make a serious move like this. It is amazing what you have done. I want to thank you so much for spending the time to describe your journey of discovery and your commitment to the contemporary jewelry field.