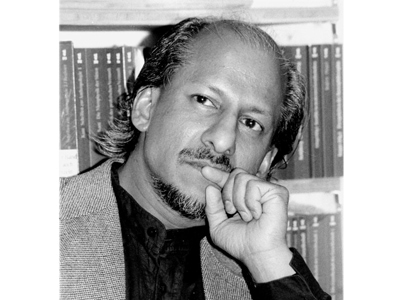

Hence my excitement when Pravu Mazumdar agreed to develop his own thoughts on the role of the critique, in a two-part essay titled Against Criticism. This is the second part of Pravu’s essay, in which he focuses on the critical writing of Bruce Metcalf.

6.

In the following two sections, I would like to flesh out some of the ideas developed in part 1 of my essay by taking a close look at some of the entries on the website of Bruce Metcalf, a “studio-jeweler” in his own terms, and a writer on jewelry-related issues.[1] To avoid any misunderstanding: I am not discussing Metcalf because I believe that he is in any way representative of current critical practices related to contemporary jewelry. I am discussing his views merely as a contrasting foil for bringing into sharper focus the idea of critique as opposed to criticism, which I have tried to delineate in part 1. Metcalf’s ideas concerning the matter run quite contrary to mine.

Metcalf is not only an experienced maker and teacher in the art and craft of jewelry and metalsmithing, but also a passionate advocate of certain principles of its production and evaluation, creating over the years a formidable mass of texts, in which he regards the practice of making jewelry as a craft in the first place and as art only in the second. It is Metcalf’s dual competence as a jeweler and writer that makes his texts so instructive to people like me, who approach the subject from “outside,” not as makers, but as fans with a more-than-ordinary interest in jewelry and its role in the lived lives of human collectives. Nonetheless, when it comes to the question of evaluation, Metcalf’s perspective narrows down to a veritable ideology of criticism, as we shall see in short.

To follow Metcalf’s reflections, it might be useful to keep in view his fourfold categorization of jewelry: (1) costume jewelry, which is “inexpensive, glitzy, usually mass-produced, and designed to coordinate with fashion”; (2) social jewelry, consisting of “highly conventional objects like engagement rings that are designed to communicate in ordinary social codes”; (3) art jewelry, meaning “objects specifically designed to be compared to cutting-edge visual art, and that hold an extended discourse with history and theory”; (4) studio jewelry, which is – as Metcalf believes – jewelry meant to be worn in the traditional sense, devoid of the far-fetched theoretical and historical involvements of art jewelry, yet imbued with a “modern taste” and standing in opposition to the mass production of jewelry.[2]

With such distinctions in mind, Metcalf unfolds his thinking on the issue of evaluation, attaining a kind of tautological certitude as long as he restricts himself to what I would like to term the “craft dimension” of jewelry, but getting caught up in woolly categorizations the moment he turns to its “art dimension.”

Metcalf begins by emphasizing his faith in the indispensability of judgment, the absence of which would “set off a race to the bottom.”[3] Another “argument” he keeps coming back to is consensus, implying that the inevitability of a practice like judgment issues from the sheer force of its popularity: “Everybody is judged. And everybody agrees that this is necessary and unavoidable.”[4]

In trying to work out the norms of judgment, Metcalf initially dwells upon the “craft-ness” of a work, as he terms it,[5] and names five “criteria” for judging crafts in the same way as works of art are judged. These are: (1) originality, meaning a respect for copyright regulations in the course of producing a work; (2) ethical sourcing of materials, implying, for instance, a rejection of blood diamonds; (3) sustainability, demanding an ecologically compatible sourcing of materials; (4) good craftsmanship, meaning that a work has been produced in conformity with certain technical traditions determining a craft; (5) durability, meaning that a properly crafted thing like a chair does not simply collapse prematurely.[6]

We have here a motley collection of criteria, which boil down to a tautology if subjected to closer scrutiny. The first three criteria concern the legal, moral, and political aspects related to the production process, which, even if extended ad libitum, must remain external to the craft dimension of a work. The fifth criterion represents a subcategory of the fourth, as Metcalf himself admits, so that it has no business turning up in such a list. What thus remains is criterion number four, amounting to an empty judgment of the kind: Good craftsmanship is good craftsmanship.

In other words, formulating the norms of criticism is not as easy as Metcalf would have us believe. And if we do at times encounter quick and convincing verdicts like “this is really bad work,” their success ultimately depends not on a handful of rules, but on a complex prior knowledge and experience in dealing with such works. If the “judge” were to put the process leading to such verdicts into words, the result would certainly not be criticism in my sense of the word, but critique, understood as a description growing in strength as it gains in detail and nuance.

Instead of addressing such questions, Metcalf reintroduces the category of originality as a means of identifying true art as such. All true art, he says, has to be original. Such a statement not only ignores critical traditions associated with names like Nietzsche/Benjamin/Adorno/Warhol, questioning all those run-of-the-mill creeds of “originality” and “genius” that continue to haunt us since the eighteenth century, but also cultural movements like fake-art, which have been attempting to deconstruct the very idea of originality in art since the 1980s. An example of this in contemporary jewelry is the work of the Australian goldsmith Robert Baines, who applies traditional technologies like granulation to create jewelry that he associates with fictitious historical sources like a Phoenician gold hoard on the north-eastern coast of Australia (2000). Another example is the exhibition entitled The Gallium Hoard from Obertraun (2011), in which Peter Bauhuis, a German goldsmith, presented his own jewelry-work under the banner of a fake Central European civilization allegedly belonging to the early Iron Age.

However, Metcalf decides at this point to let the cat out of the bag and name some of his favorite jewelers, with which the issue of judgment suddenly attains a rather welcome tangibility. He enumerates a group of mainly American jewelers producing works that he admires, adding that such admiration “is widely shared” and asserting once again his faith in consensus.[9]

In short, writing about works we have decided to reject does not require much more than the knowledge of a few rules that we are not prepared to question, as well as a certain negative passion aroused in us by the work itself. Writing about art we truly admire requires courage, for in doing so we expose ourselves no less than the work we are presenting. It is therefore not surprising that Metcalf takes recourse to consensus at the very moment that he reveals what he really likes.

Thus, after going through a maze of fruitless judgmentalism, Metcalf finally comes around to naming some of the works to which he can attribute being. This can only be welcomed as a turning point, at which criticism begins to falter and critique can begin its feast.

7.

One of the artists Metcalf admires is Pat Flynn. In the essay Pat Flynn: A Really Good Goldsmith,[10] he describes Flynn as a studio jeweler, which means neither an art jeweler nor a traditional goldsmith, since he is endowed with a modern taste allowing him to make his own creative decisions about forms. His works are crafted carefully, slowly, and in small numbers. Unlike art jewelers in the U. S., Metcalf contends, Flynn does not despise his customers and is entirely devoid of the ironies so typical of Postmodernism. Nonetheless, he creates new forms, simply because he believes that they are beautiful. At the same time he values repairing jewelry as an etude in craftsmanship and with true concern for the “life of jewelry”, poignantly aware that jewelry can wear out by being worn and that the sentiments attached by the wearer to an object must be taken seriously.

Thus, Metcalf undertakes a critique in the best sense of the word, as long as he sticks to his description of Flynn’s work. However, he also deems it necessary to defend Flynn’s work against what he calls “art jewelry,” which in his view tends to be arrogant toward customers and contemptuous toward craft in its desperation to find a place in “the grab-bag of popular culture” or to launch “extended discourses with history and theory.”[11] As any lover, Metcalf cannot resist his own prejudices issuing from a jealousy typical of the lover. At such points, the art of critique, born of his admiration for Flynn’s work, tips over to a verdict devoid of knowledge and nuances.

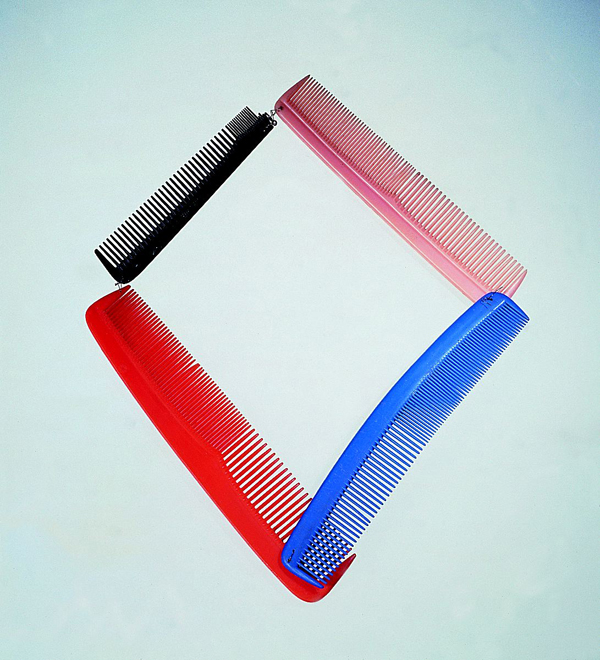

I wonder, though, how such criticism could hold its ground if it encountered pieces like the Obscure stripes (2013) by British-born Australian jewelry maker Linda Hughes, whose work consists mainly of exquisitely crafted and exquisitely wearable brooches with stripes, based on more than a decade of research into art history and semiotics in the context of Western visual traditions.[12] How could it resist a neckpiece by Bernhard Schobinger—who certainly needs no introduction—like We are only really free when we are neatly combed (1983), consisting of four colored plastic combs linked together with cobaltite wire, to be worn as a statement merging with the person of the wearer?[13]

I guess the impotence of Metcalf’s criticism is best demonstrated in his verdict on Otto Künzli.[14] He cuts up Künzli’s complex and nuanced work into two successive phases. Phase 1 is based on a powerful and reductivist “no” to precious metals, conventions, and tropes, which Künzli, in Metcalf’s view, hurls against any tradition or visual aesthetics external to the essence of jewelry. Phase 2, beginning in 1991 and lasting to the present, is based on a weak “yes” with a “non-committal, drifting quality” and producing “friendly caricatures, pared-down geometries, experiments with restrained luxury” without any “overriding idea guiding his investigations.”[15] What we have here is a quick, terse judgment based on the expectation that a “no” is only a “no” and can only be followed by a “yes.” Such a judgment is obviously rooted in one of those barren discourses so typical of criticism: far removed from the real objects populating Künzli’s world and from that delirium of description, which captivated us in Metcalf’s treatment of Flynn’s jewelry.

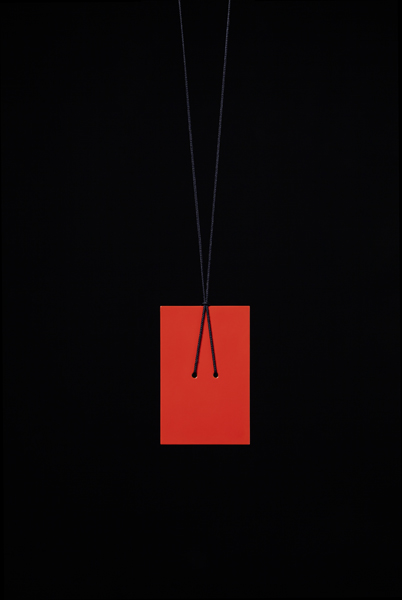

But is Künzli’s Drawing pin brooch (1980) really nothing more than a minimalist thumbtack attached to a wearer’s body, devoid of symbolism or meaning, as Metcalf rules?[16] A critique of such an object would in my view have to include something like a phenomenology of the “red dot” in our contemporary Lebenswelt. It would have to consider that a red dot is used to transmit the information that an object has just been sold in the art market and is not available for a second act of selling. This would reveal that Künzli’s piece is not merely a “no,” as Metcalf would have it, but that it has the power to transform its wearer visually into a commodity that has just been bought: bought over by the artist, bought over by the very act of buying.

Another example of the limitations inherent to criticism is Metcalf’s treatment of one of Künzli’s latest works, the three Nare pendants (2008–2011), crafted in a lengthy process that lasted over a period of several years. It is noteworthy that Metcalf does not fail to see all the details connected with the craft aspect of the pieces and yet misses the main point, simply because he is ridden by the criticist passion. He sees that the truly exquisite lacquer applied by the Japanese urushi master Murose Kazumi to the rectangular pieces of gold consists of 12 layers, that the Japanese title of the pieces “refers to the quality of having been worn down by years of handling, and is thus associated with the sweat and grime of the hand.”[17] Yet his criticism obstructs the insight that these pieces have their transience “built into” them as part of the concept generating them. Metcalf complains, that there is “no sweat or grime here, … just purity. The piece is simply a presentation of beautiful lacquer and the knowledge of the underlying gold. That’s it.”[18]

The blindness typical of such criticism becomes evident the moment we realize the nature of the point missed. For Metcalf fails to distinguish between the instant of presentation of a piece, representing its zero degree of use, and any other future instant, in which its wear and tear will have begun to show. It is between such instants that the piece unfolds its life as a thing worn by a human body. It is this flexible, yet specific, duration that is incorporated into the Nare pendants as their essential conceptual element. In one of Künzli’s most famous early pieces, Gold makes you blind (1980), the slow decay of the rubber bangle finally reveals the gold ball inside its hollow. However, the piece is associated with the artist’s guarantee that the rubber sheath will be replaced the moment a tear appears on its surface. In Nare, the concept gains in radicalism and subtlety at the same time. Its subtlety lies in the fact that it takes much longer for the gold to show through the 12 layers of lacquer. In fact, one of the essential properties of urushi lacquer consists in the fact that it does not crack, but thins out with use, so that the gold can only reveal itself over the years, gently and gradually as a kind of inner glow showing through the urushi. On the other hand, the radicalism of the Nare pendants is manifested in the fact that the decay will never be evened out by the artist as in the case of Gold makes you blind. Instead, the vector of transience will be retained and will reveal itself with increasing clarity. In addition and in opposition to the concept of Gold makes you blind, the issue at hand is not simply to reveal transience and gold, or, in a symbolic sense, the gold of transience, but to equip transience itself with a new value: nare, which simply means the nobility of a piece emerging from its use and becoming manifest as a patina born of age. Between the concepts of Gold makes you blind and Nare we do not merely discern the rupture between a simplistic “no” and an equally simplistic “yes.” The relation between the two pieces is at the same time a continuity and a break. On the one hand, the later piece, belonging to Metcalf’s phase 2, plays with transience just as the earlier one in phase 1. On the other hand, the later piece is meant to manifest over the years an irreversible and yet valuable kind of transience that can be pitched against rampant capitalist ideologies like disposability with respect to artefacts and juvenism with respect to humans. All such complexities escape Metcalf with an inevitability deriving from the reductive nature of criticism.

The moralism implicit in criticism might be practical. It might involve the laudable intention of securing the power of good over evil. But it is certainly not compatible with knowledge.

[2] Bruce Metcalf, “Pat Flynn: A Really Good Goldsmith,” 1998, http://www.brucemetcalf.com/pages/essays/pat_flynn.html.

[3] Bruce Metcalf, “Can Production Craft Be Judged?” 2014, http://www.brucemetcalf.com/blog.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Metcalf, “ Pat Flynn.”

[6] Metcalf, “Can Production Craft Be Judged?”

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Metcalf, “Pat Flynn.”

[11] Ibid.

[12] See Linda Hughes, The Obscure Stripe (Munich: Galerie Biro, 2013).

[13] See Bernhard Schobinger, Jewels Now, eds. Roger Fayet/Florian Hufnagl (Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2003), 92.

[14] See Bruce Metcalf, “Thoughts on the Coronation of Otto Künzli,” 2014, http://www.brucemetcalf.com/blog.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.