Susan Cummins: Christine, please tell the story of your background and how you knew you wanted to make jewelry.

Christine Matthias: It was only after completing a commercial apprenticeship and studying interior design in Hanover that I took up my studies at Burg Giebichenstein´s jewelry department. During my studies in Hanover, I got interested in jewelry making and started to learn some of the necessary skills. I spent a semester at the Politecnico in Milan and finally completed my interior design studies with a diploma, but I already knew that I would do something different. I wasn’t interested in furnishing medical offices or fair stalls.

I drew a lot during that period, and so that was my preparation for studying in Halle. I didn’t want to just design things. I wanted to be involved in making them. For me, making jewelry combines the artistic process with a very precise and concentrated sort of work. I enjoy being independent in what I do, and I find it important that everything is in my hands from the first idea to the finished piece.

It was not obvious that I would take up an artistic profession. Rather, I approached it gradually. I grew up on a farm in West Germany, a very rural environment with lots of animals. That was a strong influence.

Can you describe the city of Halle? What is the feeling of the city? Are there remnants of the Soviet occupation? And what are the important industries of the city?

Christine Matthias: Halle is full of contradictions and discontinuities, an interesting yet underrated city. It is not a wealthy place. Today, Saxony-Anhalt is one of Germany’s structurally weak regions. Halle’s past, however, was very rich with well-off, educated citizens and one of Germany’s oldest universities.

In more recent times, it is a workingman’s town, with opencast mines, heavy industry, and a chemical industry. During GDR times, Halle-Neustadt was built next to the old town, a concrete slab city that was meant to become an ideal socialist town.

All these changes are visible in Halle’s architecture, making it a very interesting place. You see wonderful early twentieth-century villas and concrete slab housing estates right next to each other. The city was not destroyed during the war, but the German reunification happened just in time to save a lot of the old buildings.

Halle has a strong character. It is a straight and honest place. I grew up in West Germany, and many things were completely new to me when I arrived in Halle a few years after the wall came down. But, I soon felt very comfortable here.

What was your experience of studying under Dorothea Prühl?

Christine Matthias: I had no preconceptions before I started. I was looking forward to the intense fundamental education offered at Burg Giebichenstein, including extensive nature studies as well as introductions to painting, sculpture, and other fields. And I wanted to learn the craft of goldsmithing.

Dorothea Prühl taught me not to be satisfied too easily, to look into things carefully and in depth. That can be hard at times. It is an uncompromising approach that nourishes doubt and a very high standard to apply to one’s work and to one’s self.

I had a great time studying at Burg Giebichenstein. There was an intense work atmosphere in the jewelry class. As students, we were free to develop things and to let them grow. We developed a great passion for our work, and we shared those feelings.

I don’t think I could have had a better teacher, and I am very grateful to have studied with Dorothea Prühl. She conveyed to us that there was a sense in our work. It was only during my studies that I understood how one’s work and one’s personality really are a unity.

What is a typical day for you?

Christine Matthias: In order to get a good start, I need structure and rituals. It takes a long time before I am really ready, and if I can, I take the time and start a little leisurely. After doing some errands, I leave for my workshop around lunchtime. It is only a few minutes walk from my flat. To start working also takes time. If I’m lucky, I get into the flow, which is a wonderful state. It is just as difficult to stop, and I often leave the workshop quite late.

For this collection of jewelry, you have chosen to make simple shapes in silver, and then adorn some with small patterns of stones. Is this a new idea for you?

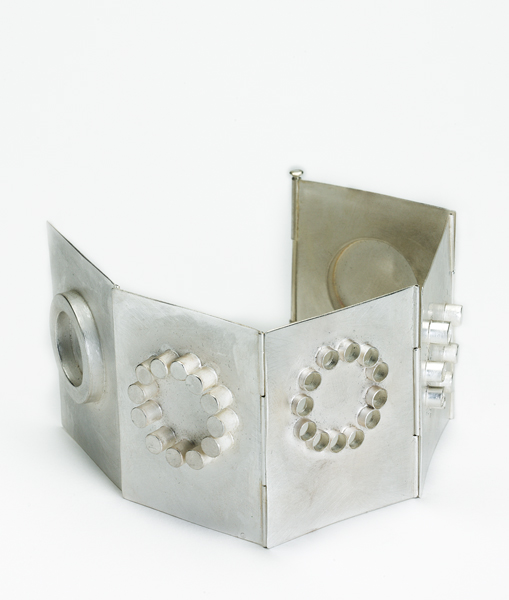

Christine Matthias: For most of my designs, I start out with symmetrical forms. I try to attain a delicate simplicity, which I can best express in clear, often angular, shapes. They are balanced by small details, little disruptions of the symmetry that break up the austerity of the shapes. In that sense, the small patterns of stones represent a continuation of the idea.

My intention is to show the stones in different contexts. I use them as graphic elements. They are delicate and linear, but also spiky and resistant. And then, I was also thinking of feathers or thorns, too, and the idea seemed to make the pieces alive. I liked that. The fundamental challenge is to find a simple form that is neither boring nor irrelevant.

What do you like about working with silver? Can you describe your process?

Christine Matthias: Silver is a wonderful material as regards working and aura: brilliant, delicate, and almost white. I want my jewelry to have that same radiance. I enjoy the metal’s resistance, so I don’t really feel the need to use other materials. Sometimes, I think I should try that, but my challenge is to use classical goldsmithing techniques and materials to create contemporary jewelry. I do sketch my ideas, but the sketches are only visual notes. Very soon I start on the material to follow the first lines of thought, for instance using the metal to make a form visible. I see it clearly in my mind, but things often take off in different directions on the way. It is exactly that aspect which makes the process interesting. I get new ideas that way. It is important to continually discard and to start again.

Some of your pieces are quite large. Why?

Christine Matthias: That’s a surprising question. I don’t find my pieces that large. I might not find the practical aspects of wearing some of my pieces so important, so I feel free to choose a large format. And my studies have surely left their traces: one of Burg Giebichenstein´s traditions is to make very large pieces of jewelry.

Can you name a couple of jewelers you think are really fantastic? Why?

Christine Matthias: You won’t be surprised to find me name Dorothea Prühl first. I admire her work, and I really like her as a person. Her jewelry is impressively simple. The enormous truthfulness of her personality becomes apparent in her work. I also find Francesco Pavan´s works very appealing. I remember seeing one of his brooches in person: delicate lamellae that are aligned to a shape. The longer I make jewelry, the less often I get really excited about a piece I see. But I found the beauty and fragility of this piece very touching. And there is Philip Sajet´s jewelry, which I greatly admire. His pieces have an exciting splendor and opulence. He combines artistic freedom and craftsmanship in a very interesting way. I also like the humor of his earlier pieces, such as putting enameled sausages on a necklace.

What are you reading?

Christine Matthias: I try to keep track of what’s happening, and I am interested in books that examine the state of the world. After reading Jonathan Safran Foer´s Eating Animals, I will now go on to Melanie Joy’s Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows. I also read on socio-psychological topics, books by Alice Miller or by psychoanalyst Hans-Joachim Maaz. I don’t manage to read as much as I would like to. Sometimes I also read contemporary literature by German authors, such as Juli Zeh or Sybille Berg.

Thank you.

Translation: Anna Helm