Susan Cummins: Is Fingers still a cooperative? How does it work?

Alan Preston: It was always five or six separate businesses operating collectively. One of these is Fingers. We still have five members selling their work through Fingers and we sell around 60+ makers on commission. We employ five people who do the bulk of the work selling and coordinating shows.

What is your role?

Alan Preston: My role is that of a senior partner advising on the phone where necessary and doing the internet banking. Today it was buying the wine for the opening for Matthew McIntyre-Wilson and bidding farewell to Octavia Cook, another jeweler, on Monday.

What is your background?

Alan Preston: Initially I was a research psychologist. I then became a self-taught jewelry maker in 1972 or 1973. After leaving Callan Park Hospital in Sydney and my occupation as a Research Psychologist, I travelled through Southeast Asia. That was in 1971. I reached the United Kingdom in mid-1972. That year I enrolled in a jewelry skills course at the Camden Institute and saw the work of contemporary jewelers like Wendy Ramshaw and Gerda Flockinger at Electrum Gallery, the Crafts Council and Camden Lock. After returning to New Zealand in 1973 I continued to make. Incidentally, Callan park is now Sydney College of Arts and Unitec, where I am Adjunct Professor, is also a former psychiatric hospital. I started Fingers with some other New Zealand jewelers in 1974.

Alan Preston: Some younger men are still using the materials. We represent Warwick Edgington, Ben Beattie, Rob Uprichard, Craig McIntosh, Chris Charteris and Jo Sheehan, who all work in these materials.

Thanks Alan. Now I have some questions for Matthew McIntyre-Wilson. Can you tell me the story of your family background and professional training?

Matthew McIntyre-Wilson: One grandfather enjoyed a successful career as an artist and my other grandfather was an architect. I feel very lucky to come from such a creative family that has always been supportive of my work. I completed a two-year Craft and Design course through Whitireia Polytechnic in the early 1990s, followed by a two year Visual Arts and Design Diploma at Hawkes Bay Polytechnic. They were not courses that focused solely on jewelry, although I particularly enjoyed working with the small scale of jewelry.

Since you are now teaching at Whitireia Polytechnic, can you give me an example of one assignment you give your students that really gets their imaginations working?

Matthew McIntyre-Wilson: My role at Whitireia is as technician and tutor support to Peter Deckers, so I don’t really set any assignments myself. I am more of a critical eye for the technical aspects of the students’ making. It is a great environment to be part of and I enjoy the interaction with other jewelry makers and the supportive environment. I really like the diverse range of creative people that contemporary jewelry making attracts. It makes for some great workshop banter.

Matthew McIntyre-Wilson: For the past eleven years I have lived with my young family in a wonderfully eclectic place designed by renowned architect Ian Athfield. My partner was working for the architectural office as an Interior Designer and when an apartment became available on the hillside we jumped at the opportunity, being pregnant with our first child at the time. I think the main idea of Ath’s vision is to create a place that instills a strong sense of community whilst allowing inhabitants to maintain their sense of privacy. The result is one giant rambling adaptable ‘complex,’ full of apartments, courtyards, architectural office, Ian and Clare’s house and lots of steps. The complex is situated on the northwestern hills of the Wellington Harbor, with a breathtaking view. It is an inspiring place to live and work, with lots of wonderful people around.

You are well known for using a traditional Maori weaving technique to make jewelry and other objects. Where did you learn this?

Matthew McIntyre-Wilson: I first learned to weave while completing my Diploma in Visual Art and Design in Hawke’s Bay during the 1990s. I had an inspirational friend called Rangi Kiu, who was known for his fine weaving skills. He used to work in a whare raranga (weaving house) above the Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic, the whare (house) was covered in beautiful woven panels. It was there I would watch Rangi weave his amazing work and how I first learnt how to weave. My first attempts at marrying jewelry and weaving together were incredibly crude compared to my works today. I initially used cut strips of copper sheet, which was not very maker-friendly. Years later, when my first daughter was born and I was primary caregiver, I found that weaving was something I was able to work on while she was asleep without me being out of earshot in my workshop. It was during this time that I was able to adapt and refine my techniques to allow me a finer weave. Maori weaving is not traditionally made using metal, traditional techniques are all based around using plant fiber. Being aware of this and having knowledge of working with metals, I was able to adapt my weaving techniques to suit.

Matthew McIntyre-Wilson: I guess I have always followed my interest in patterns, exploring new patterns as well as traditional ones. I find it very interesting with pattern that a subtle shift can result in a completely different effect.

Is that what you will be showing at Fingers?

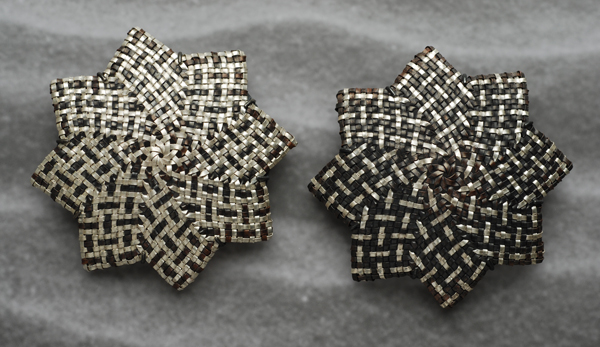

Matthew McIntyre-Wilson: The work I am currently showing at Fingers is a range of pairs of objects that are all woven, including cuffs, small kete (baskets) star shaped brooches and poi necklaces. By using the pairs the subtle shifts I mentioned above can be easy to recognize in some of the pairs.

The work called The Price of Change is intriguing and I am wondering if you can explain a bit more about the idea behind it.

The history of many New Zealanders is like my own, a mix of Maori, Scottish, Irish and British and the potent images found on the coins create various interpretations dependent on an individuals heritage or perspective of this country. In New Zealand, where there is such a turbulent history between the crown and Maori, there are numerous stories and perspectives to be told. As a collection, it feels open-ended to me as far as the compositions go. It is constantly evolving. It holds the same appeal to me as weaving and pattern making, the restrictions at first seem, well, restricting, but there is a sense of freedom within that. The choices that you make in order to restrict yourself and then the limits you can stretch out to, is a form of creativity I enjoy.

Matthew McIntyre-Wilson: It is difficult to select just one book on jewelry. But one that I particularly enjoy is Pacific Jewellery and Adornment by Richard Neich and Fuli Pereira. Often the types of books I am drawn to are not focused solely on jewelry, they are probably more likely to be books focused on weaving. One such book is Te Aho Tapu: The Sacred Thread by Mick Pendergrast.

How about a favorite book on the history of Maori tribes of New Zealand? Or maybe a novel with Maori characters?

Matthew McIntyre-Wilson: The Coming of the Maori, by Te Rangi Hiroa, is a book I appreciate, along with Maori: A Photographic and Social History, by Michael King.